Let’s Dismantle a Big One: Original Languages and the New Testament

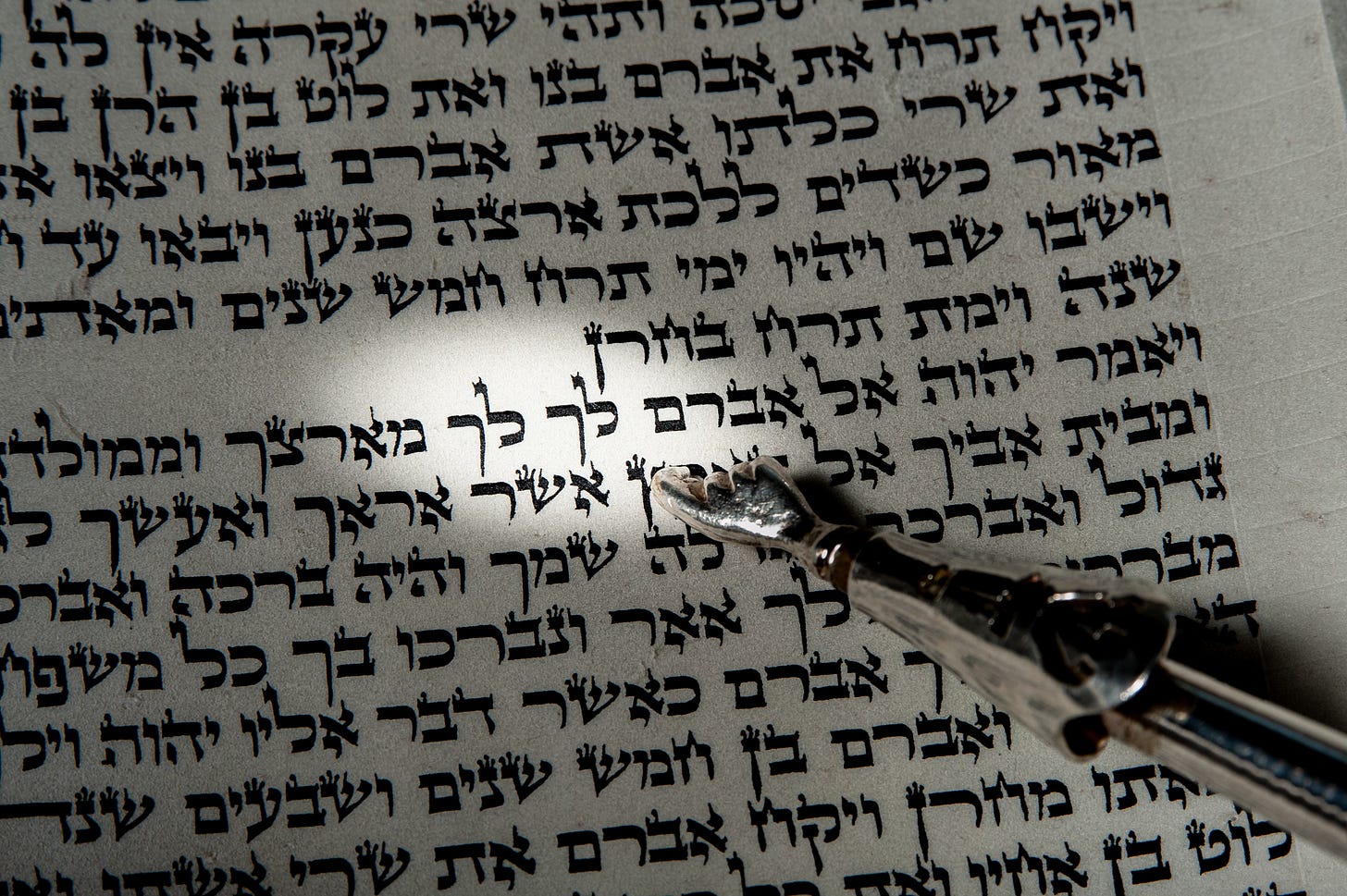

Listening Again: How Hearing the New Testament in Hebrew Restores Its Heart

Editorial Note — Research Brief

This piece departs from my usual conversational style. Treat it as a collegiate research brief: sourced, structured, and meant to sharpen method. The goal isn’t to win an argument but to clear the table so we can eat the bread of Scripture without the crumbs of bad assumptions.

A Quiet Assumption That Shaped a Century

Some ideas linger so long they start to feel like facts. One of the biggest is this:

“Aramaic was the language of Jesus and the Jews of the first century; Hebrew was basically ceremonial.”

From that assumption, a thousand commentaries took flight. Yet when you press into the evidence—inscriptions, scrolls, rabbinic sayings, even the way the New Testament itself uses the word Hebraisti—the picture sharpens: first-century Judea and Galilee were multilingual, and Hebrew was very much alive.

This matters. If you mis-hear the language of a people, you mis-hear their heart. And when the heart you’re listening for is Israel’s, you risk mis-hearing Yeshua Himself.

Start with Proportion: The New Testament Is Small—on Purpose

Our Christian Bibles devote roughly three-quarters of their pages to the Tanakh (Hebrew Scriptures) and about one quarter to the New Testament. The apostolic writings are a slender capstone set atop Israel’s massive foundation.

So when we ask, Which language best unlocks the New Testament’s meaning?—the answer must begin with the language of the world it is explaining: Hebrew, and the thought-world of the Tanakh and the Sages.

The Language Landscape Yeshua Walked

When scholars revisit the data without 19th–20th century bias, a clearer landscape emerges:

Three tongues in play: Greek (commerce/administration), Aramaic (regional lingua franca), and Hebrew(Scripture, teaching, legal identity).

Dead Sea Scrolls: The overwhelming majority are Hebrew, with smaller Aramaic and Greek portions.

Inscriptions and coins: Hebrew appears publicly, not just liturgically.

Rabbinic voice: The Mishnah (c. 200 CE) records Mishnaic Hebrew as the natural speech of halakhic discourse.

Scholarly Consensus Emerging

The “exclusive Aramaic” model came from outdated assumptions.

Hebraisti in ancient Greek sources nearly always means “in Hebrew.”

Sociolinguistic studies of Galilee confirm Hebrew’s robust use in teaching and law.

The Scrolls show Hebrew as a living continuum, not a fossil.

Why the Assumption Tilted Toward Aramaic

Western scholarship privileged Greek as “civilized,” assumed Aramaic was the people’s tongue, and demoted Hebrew to liturgy. Translators reinforced this by rendering Hebraisti as “in Aramaic.”

The modern correction doesn’t deny Aramaic—it simply restores Hebrew to its rightful place beside it.

Where Hebrew Clarifies the New Testament

Hebraisti ≠ “Aramaic.”

John’s Gospel and others mean exactly what they say—in Hebrew—revealing direct linguistic insight.

Halakhic discourse and parables.

Yeshua’s teaching matches tannaitic forms: mashal, kal va-ḥomer, gezerah shavah—all Hebrew reasoning.

Legal and covenantal terms.

Concepts like forgiveness, release, debt, and teshuvah pulse with Hebrew idiom.

“Eli, Eli …” and legal tone.

Re-hearing Psalm 22 through Hebrew law language reveals deeper covenant context.

Naming & place-terms.

When the NT pauses to say “in the Hebrew,” it signals that the Hebrew form matters for meaning.

The Mishnah as a Living Key

Mishnaic Hebrew isn’t late rabbinic dust—it’s living speech from Yeshua’s contemporaries.

Its grammar differs from Biblical Hebrew, but its world is the Gospels’ world: vows, sabbaths, oaths, purity laws.

Practical Tip:

Read a tractate like Avot while studying Gospel halakhic debates. The cadences, logic, and compassion will start to sound familiar.

What This Does—and Doesn’t—Mean

✅ Do: Read the NT as a Jewish text, tethered to Hebrew thought.

✅ Do: Hear Mishnaic Hebrew cadences when studying parables and disputes.

❌ Don’t: Erase Aramaic or Greek. Recognize a multilingual world.

✅ Do: Embrace the both/and, with Hebrew restored to its covenant weight.

A Brotherly Challenge: Return to the Root to Understand the Fruit

The New Testament is a small book resting on a vast one.

Read the capstone apart from the pillars and the geometry distorts.

Set it back upon the Tanakh, and the picture resolves.

Let the Tanakh define your dictionary.

Let Mishnaic Hebrew refine your hearing.

And let Israel’s language lead you home to Israel’s God.

Questions to Carry into Study

How would a Hebrew speaker say this line the NT quotes from the Tanakh?

What Mishnaic vocabulary lies behind legal and purity terms?

Where does translating Hebraisti as “Aramaic” bias my reading?

Which Dead Sea Scrolls parallels illuminate this phrase or idiom?

What do first-century coins and inscriptions say about public literacy in Hebrew?

A Layman’s Guide: Translating the New Testament into Hebrew (and Back)

For the diligent reader who wants to trace Hebrew rhythm behind Greek words:

Base text: Use BibleHub Interlinear, STEP Bible, or Blue Letter Bible to see Greek with Strong’s numbers.

Find Semitic echoes: Compare each Greek term’s LXX usage to its Hebrew root.

Hebrew lookup: Use BDB or Even-Shoshan for Hebrew definitions.

Reconstruct: On Lexilogos, type a simple Hebrew version of your verse; keep syntax Mishnaic.

Back-translate: Render that Hebrew back into English, preserving rhythm.

Cross-check: Consult Buth & Notley, Segal, Wilcox, or Blizzard for parallels.

Journal: Record verses where Hebrew reconstruction clarifies meaning.

Example:

Matthew 5:3 — “Blessed are the poor in spirit.”

Greek: Makarioi hoi ptōchoi tō pneumati

Hebrew: Ashrei ha’anavim baruach → “Favored are the humble in spirit.”

Ashrei echoes Psalm 1’s covenantal happiness.

Recommended Tools:

STEP Bible · BibleHub Interlinear · Blue Letter Bible · Sefaria.org · Lexilogos Keyboard

Follow these steps, and the New Testament will begin to speak with its ancestral warmth again.

A Closing Contrast to Ponder

Modern habit: start with Greek grammar, consult Aramaic, sprinkle “Jewish background.”

Recovered habit: start with Hebrew Scripture, listen for Mishnaic Hebrew, then confirm with Aramaic and Greek.

The first yields clever sermons.

The second yields covenant clarity.

Selah

Have pity on the systems that severed the Church from Israel’s living voice and then wondered why Yeshua’s words felt foreign.

Let’s repent of borrowed assumptions and return to the language of the covenant family—so that grace and truth sound like home again.

Sources & Further Reading

Language Environment & Lexicon

Randall Buth & R. Steven Notley (eds.), The Language Environment of First-Century Judaea (Brill 2014).

Ken M. Penner, “Ancient Names for Hebrew and Aramaic,” NTS 65 (2019): 412–23.

Max Wilcox, “The Semitic Background of the New Testament,” in Early Christian Origins (CUP 1997).

Mishnaic (Tannaitic) Hebrew

M. H. Segal, A Grammar of Mishnaic Hebrew (Clarendon 1927).

Steven E. Fassberg & Moshe Bar-Asher (eds.), Studies in Mishnaic Hebrew (Magnes 1998).

Dead Sea Scrolls & Second Temple Hebrew

Elisha Qimron, The Hebrew of the Dead Sea Scrolls (Scholars Press 1986).

John J. Collins, The Dead Sea Scrolls: A Biography (Princeton 2012).

Israel Antiquities Authority, “Languages and Scripts.”

Hebrew-centric NT Studies

David Bivin & Roy Blizzard, Understanding the Difficult Words of Jesus (Destiny Image 1994).

Scope & Proportion

Felix Just, S.J., “New Testament Statistics” and “Old Testament Statistics,” Catholic-Resources.org.

When apostle Paul was about to be lynched in the temple by the mob in Jerusalem, he addressed them all in the Hebrew tongue and we are told that they became quiet and listened to his long speech because of it. That means Hebrew commanded respect and the whole city could understand it.

Also, when he was knocked off his horse while on his way to persecute believers, Paul specifically mentions that Jesus spoke to him from heaven in Hebrew.

I have no doubt Hebrew is the language spoken in heaven.

I think that gives something to start with. I have had Tanakh for years and recently bought the Jewish Annotated NT, NRSV. Also have The New Greek-English Interlinear NT, but not with Hebrew. I look forward to exploring!