Brother, sister—before we talk doctrine, let’s talk labels. Because the labels we inherit quietly disciple us.

We’ve been taught to call Genesis through Malachi “Old” and Matthew through Revelation “New.” It sounds simple, harmless, even helpful. But names are not neutral—they carry theology. They shape how we imagine God, how we read His Word, and how we live out our faith. The moment those two words—Old and New—entered the vocabulary of the Church, they began teaching us something God never said: that what came before is inferior, outdated, or replaced.

And that misunderstanding—born not from revelation but from human editorial hands and theological agendas—has done more to fracture the unity of Scripture than almost any heresy in Christian history.

The Problem With “Old” and “New”

“Old” implies obsolescence; “new” implies replacement. But the covenantal reality of Scripture is not about discardingwhat came before—it’s about renewal, continuation, and fulfillment.

The “Old Testament” is not obsolete law; it is the living revelation of God’s covenant character. The “New Testament” is not a replacement contract; it is the consummation of what was promised long ago. When the prophets spoke of a “new covenant,” they were not talking about a novel document detached from the Torah, but about the same covenant deepened, internalized, and made living through the Spirit of God.

Yet, once translators, publishers, and theologians began categorizing Scripture as “Old” and “New,” the implication crept in: old means gone, new means arrived. It was subtle—but over centuries, that subtlety became dogma.

Now, in countless pulpits, seminaries, and Bible studies, the idea persists: “We don’t live under the Old Testament; we live under the New.” That statement, though familiar, is foreign to the heart of God.

Brit Ḥadashah

— The Covenant Renewed, Not Replaced

Let’s look at the Hebrew phrase that started this whole discussion.

In Jeremiah 31:31, God declares:

“Behold, the days are coming, says the LORD, when I will make a new covenant (brit ḥadashah) with the house of Israel and the house of Judah.”

At first glance, we hear “new” and assume “brand new,” as in something never before seen. But the Hebrew word חָדָשׁ (ḥadash) carries two distinct meanings in biblical usage:

New in time — something freshly made or unprecedented (as in “a new king arose over Egypt”).

Renewed or restored — something made new again, refreshed, or brought to its intended fullness (as in “renew our days as of old,” Lam. 5:21).

In the context of covenant—where God has already sworn eternal promises to Israel—“new” cannot mean “different” or “replacement.” God doesn’t break His word. He renews it.

So brit ḥadashah should be understood not as “a completely new covenant” but as a renewed covenant—the same divine bond, now written deeper, lived truer, and made possible by the Spirit.

Jeremiah continues:

“I will put My Torah within them, and on their hearts I will write it.” (Jer. 31:33)

Notice what is not said: God does not say, “I will abolish My Torah.” He doesn’t say, “I will replace it with grace.” He says, “I will internalize it.”

This is the heartbeat of the brit ḥadashah—not an abolition of God’s instruction but an implantation of it. The Torah moves from scroll to soul, from external command to internal desire.

It’s the same law, same covenantal love, but infused with the divine power to actually live it.

The Hebrew Root of Renewal

The root ḥ-d-sh (חדש) appears throughout Scripture in the sense of renewal.

Tehillim / Psalm 51:10 — “Create in me a clean heart, O God, and renew (chadesh) a steadfast spirit within me.”

Lamentations 5:21 — “Restore us to Yourself, O LORD, that we may return; renew (chadesh) our days as of old.”

Both speak of renewal, restoration—not creation from scratch.

Thus, when Jeremiah speaks of a brit ḥadashah, he is describing the renewing of a covenant relationship that Israel broke, not the invention of a new one that cancels the old. God does not disown His people; He revives them. He does not toss out His commandments; He writes them upon the heart.

And yet…

How “New” Became a Weapon of Replacement

Even though ḥadashah means “renewed,” in Greek translation it became kainē diathēkē—“new covenant.” The nuance of renewal faded into the background. By the time the Latin Novum Testamentum emerged, “new” had lost its Hebraic depth and gained a Roman finality—novum meaning something fresh, distinct, replacing what came before.

This linguistic shift opened the door for centuries of replacement theology. The “New Testament” was presented as the book of grace, while the “Old Testament” became the book of law—as if they were adversaries instead of allies.

This is not a linguistic quirk; it’s a theological reprogramming. The use of “new” to mean “different” gave rise to doctrines that separated the Church from Israel, grace from Torah, Yeshua from His own Scriptures.

Even more tragically, it gave rise to a Christianity that forgot its roots. The very people through whom salvation came were deemed obsolete, and the covenant God swore as “everlasting” (Gen. 17:7) was rebranded as expired.

So yes, even though brit ḥadashah is profoundly about renewal, its translation and usage have been weaponized to erase the old—to replace the foundational revelation of God with a system of human design.

A Living Example: The Catholic Young Man

A few weeks ago, a Catholic young man visited my men’s group—eager, sincere, polite. We were studying Jeremiah 31, the very prophecy of the brit ḥadashah. I read the passage aloud and asked, “What does this mean to you in light of the gospel?”

He looked at me blankly. “I’ve never read this before,” he said. “I thought the Church began in Matthew.”

His response was honest—but heartbreaking.

Here stood a believer, raised under centuries of Christian teaching, who had no idea that Jeremiah 31 is the foundationof what Yeshua proclaimed at the Last Supper. He had never been taught that the “New Covenant” didn’t begin with a manger but with a promise—spoken long before Yeshua was born.

When I began to show him how Jeremiah and Ezekiel both prophesied what the apostles later recorded, his face hardened. His tone changed. He grew defensive, then diverted the conversation to Peter and the rock, Petra and cornerstone theology. In an instant, he had pivoted from discovery to deflection.

I quietly walked away as the others politely engaged him.

And I thought to myself: this is the fruit of centuries of replacement theology—a Church that cannot hear Jeremiah without arguing about Rome. A people who cling to denominational identity rather than covenantal truth.

Why So Many Pastors Stay at John 3:16

John 3:16 is perhaps the most quoted verse in the world. But it’s also one of the most misunderstood.

“For God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son…”

It is beautiful—but it is not the whole gospel. It’s a window into a covenant story that stretches back to Genesis, yet in most churches, it’s presented as a slogan detached from its roots.

Why do so many pastors stop there?

Because John 3:16 is safe. It’s simple. It doesn’t confront the Church’s theological comfort zones.

It doesn’t require pastors to wrestle with Ezekiel 36:25–27, where God promises to wash His people clean, give them a new heart, and put His Spirit within them to walk in His statutes. It doesn’t force us to reconcile the “law” and the “Spirit” as one voice. It doesn’t require acknowledging that Yeshua’s conversation with Nicodemus—“You must be born of water and Spirit”—is a direct reference to Ezekiel.

Most pastors avoid that depth because it challenges the modern church model—a model built more on consumer experience than covenant obedience.

John 3:16 is true, but it’s not the starting point of the gospel; it’s the fulfillment of what was promised in Jeremiah 31. Without that context, it’s like quoting the final line of a symphony and calling it a song.

Jeremiah and Ezekiel Already Preached the “New Testament”

Long before Yeshua lifted the cup, Jeremiah and Ezekiel preached the same gospel message we claim to believe:

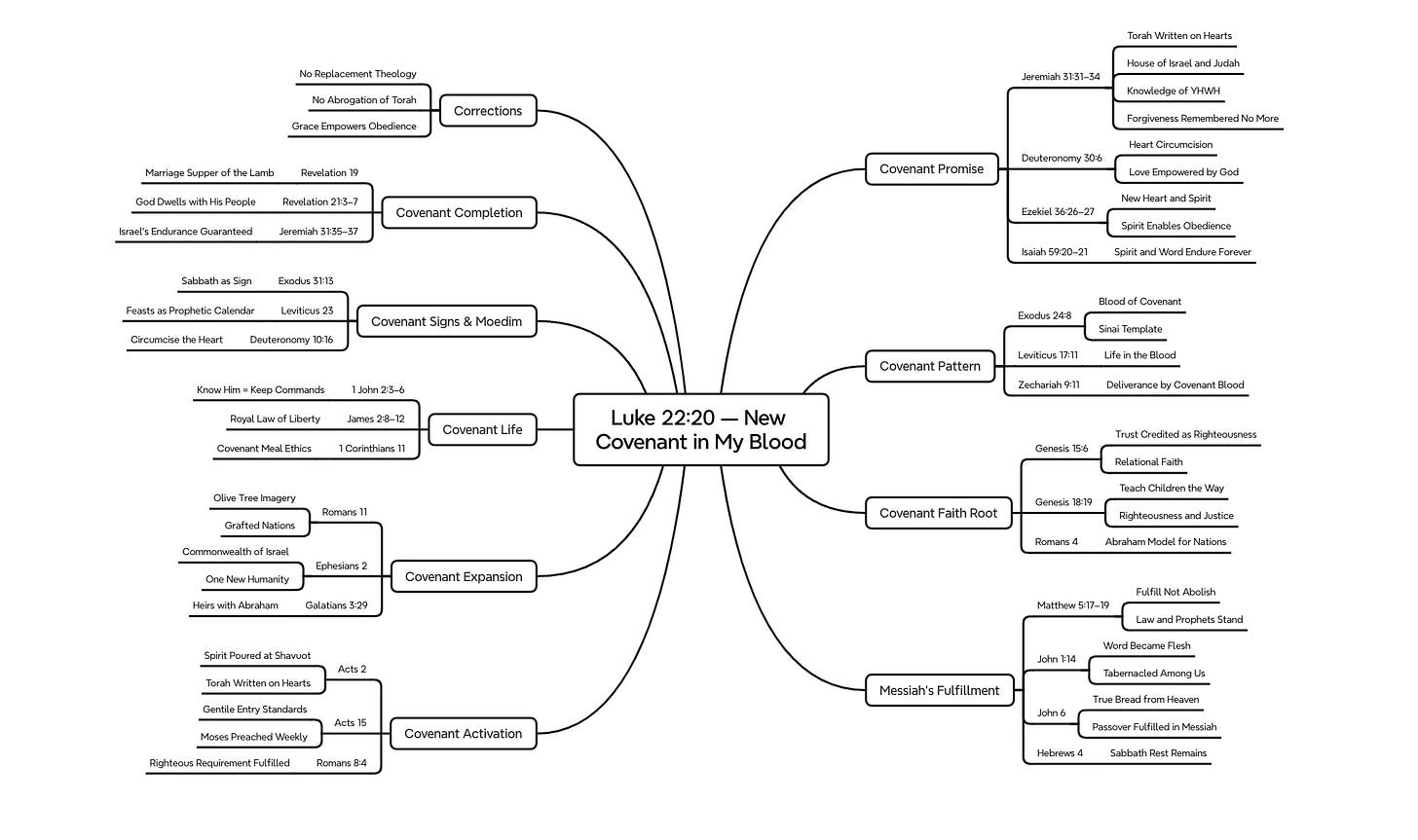

Jeremiah 31:31–34 — A renewed covenant with Israel and Judah; Torah written on hearts; sins forgiven.

Ezekiel 36:25–27 — Cleansing water, a new heart, a new spirit, and God’s Spirit causing obedience.

Ezekiel 37 — The reunification of Israel and Judah under one Shepherd-King.

When Yeshua declared, “This cup is the new covenant in My blood” (Luke 22:20), He wasn’t announcing a new religion. He was sealing what Jeremiah and Ezekiel had foretold.

The brit ḥadashah was not a surprise to heaven—it was the fulfillment of a promise that had been echoing through Israel’s Scriptures for centuries.

The Apostolic Witness: One Story, One Covenant

Yeshua and His disciples never called the Tanakh “old.” To them, it was Scripture—the living, breathing Word of God. Every sermon in Acts, every letter Paul wrote, every gospel proclamation was rooted in Torah and the Prophets.

When Paul said “All Scripture is God-breathed and profitable…” (2 Tim. 3:16), he meant the very writings most Christians now neglect.

The apostles did not invent a new faith; they declared the renewal of Israel’s faith through the Messiah who fulfilled it.

This is why the “New” must never mean “instead of.” The brit ḥadashah is not a replacement covenant—it is the same covenant written by the same hand on a new surface: the human heart.

The Human Hand in the Printed Bible

The Word of God is divinely inspired, but the packaging of Scripture—chapter divisions, titles, red letters, and especially “Old” and “New Testament”—is man-made.

These labels were never part of the inspired text. They were born from human systems—cultural, theological, and political—that shaped how we read.

That’s what I mean by the “agendized propagation of names.” Once Scripture became a printed artifact, men began shaping its categories to fit their doctrines.

The Bible’s content is divine; its compartmentalization is not. And those compartments have trained generations to think in opposition where God intended continuity.

The Call to Covenant Continuity

We must repent of this mental divide. We must learn to read Scripture as Yeshua and His disciples did: one unbroken covenant narrative, building from creation to consummation.

The Torah reveals God’s holiness.

The Prophets reveal His faithfulness.

The Writings reveal His wisdom.

The Apostolic Writings reveal His fulfillment in Messiah.

One voice. One Author. One covenant plan.

This is what it means to recover the brit ḥadashah in its fullness—not as something newly created, but as something newly realized.

A Pastoral Call to Teshuvah

Beloved, it’s time to return—teshuvah—to the unity of God’s Word.

The God who thundered at Sinai is the same God who whispered from the cross. The blood on the doorposts of Egypt and the blood on the wood of Calvary flow from the same covenantal love.

It was never “Old” versus “New.” It was always Promise and Fulfillment. Covenant and Completion. Written and Realized.

The brit ḥadashah—the covenant renewed—is the Torah written on the heart by the Spirit of the Living God. It is not the end of the first covenant; it is its awakening within us.

So let us stand once again at the foot of the mountain—both Sinai and Zion—and hear the same Voice calling:

“I will be your God, and you will be My people.”

That Voice never changed. Only our labels did.

A Final Challenge to Believers

Test everything you’ve been taught. Search the Scriptures for yourself.

Don’t let tradition, denomination, or church culture define your theology. Open the Word—the whole Word—and dig.

If your faith begins in Matthew, you’ve started in the middle of the story. If your church never mentions Jeremiah, Ezekiel, or Torah, ask why. If your pastor preaches grace without covenant, test that teaching against God’s Word.

Today’s church model—with its polished programs, sermon series, and spiritual soundbites—is not the biblical pattern. The early believers were rooted in Scripture, not schedules; in obedience, not optics.

You are responsible for what you believe. Do not outsource your discernment. Dig for yourself. Read what Yeshua read. Study what the apostles studied. Return to the covenant God never abandoned.

Because the question isn’t whether the covenant changed.

The question is—have we?

Reflection & Practice

Study the Hebrew root ḥadash throughout Scripture. Trace how often it means renewal rather than replacement.

Read Jeremiah 31 and Ezekiel 36 alongside Luke 22 and John 3. Let the continuity reshape your understanding of covenant.

Pray: “Father, renew (chadesh) within me a right spirit. Write Your Torah upon my heart. Let my obedience be love, not obligation.”

Test every doctrine you’ve been handed. Search the Word, not just the pulpit.

Teach others to see the “New Testament” not as a new book, but as the Spirit-breathed testimony of God’s renewed covenant.

May the Holy One restore our sight, renew our minds, and write His Torah deep within us.

For in the end, the story was never about old and new—it was always about faithful and fulfilled.

Good Morning Brother. I'm sickened by the cheapness of the Church today. Just say the sinners prayer and you've bought a ticket into eternal life.

Don't understand how Pastors and Teachers can make the OT irrelevant.

I'm thankful we have thoughtful writers such as yourself to clarify what todays Church is destroying.

The Good Lord is blessing you to bless the rest of us. What a beautiful thing!

Thank you once again for your insightful writing.